Romanian Revolution of 1989

| Romanian Civil War of 1989 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Revolutions of 1989 | |||||

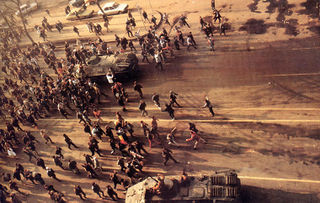

Demonstrators on the street |

|||||

|

|||||

| Belligerents | |||||

Romanian army Dissident members of the Communist party |

|||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||

| Ion Iliescu and other various independent leaders | |||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||

| 1,104 deaths | |||||

The Romanian Revolution of 1989 was a week-long series of increasingly violent riots and fighting in late December 1989 that overthrew the government of the communist president Nicolae Ceauşescu. After a trial, Ceauşescu and his wife Elena were executed. Romania was the only Eastern Bloc country to overthrow its government forcefully or to execute its leaders.

Contents |

Background

Three major components provided reason for and provoked the Romanian Revolution:

- The secret police (Securitate) were becoming so ubiquitous as to make Romania essentially a police state. There was no right to free speech or to express political or economical views other than to laud the Communist Party. It was so bad that a person could not even make jokes about the regime without the risk of arrest by the "Securitate". News, television, movies and books were censored. To get trusted news, many Romanians listened to Radio Free Europe from Western Europe or other radio stations from the West.

- Nicolae Ceauşescu's draconian austerity program, designed to enable Romania to liquidate its entire national debt in only a few years, plunged the population into painful shortages and increasing poverty. The Romanian TV channels were reduced to one channel which transmitted only 2 hours per day. Electricity was interrupted for hours, mostly at night. There were long lines at the grocery stores. All of these shortages were because electricity, food, clothes and all Romanian domestic production was exported to western countries in exchange for international currency to pay the country's debt.

- Nicolae Ceauşescu created a cult of personality, with weekly shows in stadiums or on streets in different cities dedicated to him, his wife and the Communist Party. There were megalomanic projects, such as the construction of the grandiose House of the Republic (today the Palace of the Parliament), the biggest palace in the world, and the future Communism and Ceausescu's Museum, today the Casa Radio. All these projects drained the country's finances and aggravated the already embattled economic situation. Thousands of Bucharest residents were also evicted from their homes, which were subsequently demolished to make room for the huge structures.

As in neighboring countries, by 1989 the bulk of the Romanian population was dissatisfied with the Communist regime. Unlike the other Warsaw Pact leaders, Ceauşescu had not been slavishly pro-Soviet, but rather had pursued an "independent" foreign policy. While Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev spoke of reform, Ceauşescu maintained a hard political line and cult of personality.

The austerity program started in 1980 and because of the widespread poverty it introduced, made the communist regime very unpopular. By mid 1989, Ceauşescu achieved a significant political victory with Romania paying off its external debt of about US$11 billion several months before even he had expected. However, in the months following the announcement the austerity and the shortage of goods remained the same as before. December 1989 was the last act of an end that started in 1987, in Braşov. The anti-communist riot in Braşov on 15 November 1987 was the main political event that announced the imminent fall of communism in Romania. The revolt started at the enterprise of Trucks Braşov, by a strike begun in the night of 14 November, on the night-shift, and continued the next morning with a march downtown, in front of the Council of the Romanian Communist Party. Of course, the Romanians had heard about this event through Radio Free Europe. Emil Hurezeanu tells: "I remember that Neculai Constantin Munteanu, the moderator of the show, started the broadcast: 'Braşov! So Braşov! Now it started!' This was the tone of the whole broadcast. We had interviews, information, interpretations of some political interpretations, older press articles announcing open street protests against Ceauşescu." The reprisals against strikers were rapid. The workers were arrested, imprisoned and their families terrorized, but this act of courage on the part of the workers of Braşov set the stage for future mass revolts. In this sense, from Radio Free Europe, Mr. Emil Hurezeanu says: "... All these have been turned into an offensive. The reaction of the regime was expected.. Very soon it was seen that the regime wants to hide it, to cancel it, practically not to respond to claims, not to take measures, to change anything, not to turn this protest into a public debate or even inside the party, in the Political Executive Committee. And then, the recipe of a street confrontations with the regime became the only...possible. It became the leitmotif of all the media analysis. [...] It was the beginning of an action against the system that comprises more items. It was a labor protest in a citadel of Ceauşescu, it was a antidictatorial message, it was a clear political context: the pressures of Moscow, Ceauşescu's refusal to accept the demands of Gorbachev, the breaking with the West, who changed the views towards the regime - all these have made us to believe that the beginning of the end was coming”.

In March 1989, several leading activists of the PCR protested in a letter that criticized the economic policies of Nicolae Ceauşescu, but shortly thereafter Ceauşescu achieved a significant political victory: Romania paid off its external debt of about US$11 billion several months before the time that even the Romanian dictator expected. Ceauşescu was formally reelected secretary general of the Romanian Communist Party—the only political party of the Romanian Socialist Republic—on November 14 at the party's XIV Congress. On 11 November 1989, before the party congress, on Bucharest's Brezoianu Street and Kogalniceanu Boulevard, students from Cluj-Napoca and Bucharest demonstrated with placards “We want Reforms against Ceauşescu government." The students—Paraschivescu Mihnea, Vulpe Gratian, the economist Dan Caprariu from Cluj and others—were arrested and investigated by the Securitate at the Rahova Penitentiary, accused of propaganda against the socialist society. They were released on 22 December 1989 at 14.00. There were other letters and other attempts to draw attention to the economic, cultural, and spiritual oppression of Romanians, but they served only to intensify the activity of the communist police and Securitate.

Timişoara protest

On 16 December a protest broke out in Timişoara in response to an attempt by the government to evict a dissident, Hungarian Reformed pastor László Tőkés. Tőkés had recently made critical comments against the regime to the Hungarian media,[1] and the government alleged that he was inciting ethnic hatred. At the behest of the government, his bishop removed him from his post—thereby depriving him of the right to use the apartment to which he was entitled as a pastor—and assigned him to be a pastor in the countryside. For some time, his parishioners gathered around his home to protect him from harassment and eviction. Many passers-by, including religious Romanian students, spontaneously joined in.

| History of Romania | |

|---|---|

This article is part of a series |

|

| Prehistory | |

| Dacia | |

| Dacian Wars | |

| Roman Dacia | |

| Thraco-Roman syncretism | |

| Early Middle Ages | |

| Origin of the Romanians | |

| Middle Ages | |

| History of Transylvania | |

| Foundation of Wallachia | |

| Foundation of Moldavia | |

| Early Modern Times | |

| Principality of Transylvania | |

| Phanariotes | |

| Danubian Principalities | |

| National awakening | |

| Organic Statute | |

| 1848 Moldavian Revolution | |

| 1848 Wallachian Revolution | |

| United Principalities | |

| War of Independence | |

| Kingdom of Romania | |

| World War I | |

| Union with Transylvania | |

| Union with Bessarabia | |

| Greater Romania | |

| Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina | |

| World War II | |

| Communist Romania | |

| Soviet occupation | |

| 1989 Revolution | |

| Romania since 1989 | |

| Topic | |

| Timeline | |

| Military history | |

|

Romania Portal |

As it became clear that the crowd would not disperse, the mayor, Petre Moţ, made remarks suggesting that he had overturned the decision to evict Tőkés. Meanwhile, the crowd had grown impatient, and when Moţ declined to confirm his statement against the planned eviction in writing, the crowd started to chant anticommunist slogans. Subsequently, police and Securitate forces showed up at the scene. By 7:30 p.m., the protest had spread, and the original cause became largely irrelevant. Some of the protesters attempted to burn down the building that housed the District Committee of the Romanian Communist Party (PCR). The Securitate responded with tear gas and water jets, while the police beat up rioters and arrested many of them. Around 9:00 p.m., the rioters withdrew. They regrouped eventually around the Romanian Orthodox Cathedral and started a protest march around the city, but again they were confronted by the security forces.

Riots and protests resumed the following day, 17 December. The rioters broke into the District Committee building and threw Party documents, propaganda brochures, Ceauşescu's writings, and other symbols of communist power out the windows. Again, the protesters attempted to set the building on fire, but this time they were stopped by military units. Since Romania did not have a riot police (Ceauşescu, who believed the Romanian people loved him, never saw the need for the formation of one), the military were sent in to control the riots, since the situation was too large for the Securitate and police to handle. The significance of the army presence in the streets was an ominous one: it meant that they had received their orders from the highest level of the command chain, presumably from Ceauşescu himself. The army failed to establish order and chaos ensued with gunfire, fights, casualties, and burned cars. Transport Auto Blindat (TAB) armored personnel carriers and tanks were called in. After 8:00 p.m., from Piaţa Libertăţii (Liberty Square) to the Opera there was wild shooting, including the area of Decebal bridge, Calea Lipovei (Lipovei Avenue), and Calea Girocului (Girocului Avenue). Tanks, trucks, and TABs blocked the accesses into the city while helicopters hovered overhead. After midnight the protests calmed down. Ion Coman, Ilie Matei, and Ştefan Guşă inspected the city, in which some areas looked like the aftermath of a war: destruction, ash, and blood.

The morning of 18 December the centre was being guarded by soldiers and Securitate-agents in plainclothes. Mayor Moţ ordered a Party gathering to take place at the University, with the purpose of condemning the "vandalism" of the previous days. He also declared martial law, prohibiting people from going about in groups larger than two people. Defying the curfew, a group of 30 young men headed for the Orthodox Cathedral, where they stopped and waved a Romanian flag from which they had removed the Romanian Communist coat of arms. Expecting that they would be fired upon, they started to sing "Deşteaptă-te, române!" ("Awaken thee, Romanian"), an earlier national song that had been banned since 1947. They were, indeed, fired upon and some died, and others were seriously injured, while the lucky ones were able to escape.

On 19 December, Radu Bălan and Ştefan Guşă visited the workers in the city’s factories, but failed to get them to resume work. On 20 December massive columns of workers were entering the city. About 100,000 protesters occupied Piaţa Operei (Opera Square — today Piaţa Victoriei, Victory Square) and started to chant anti-government protests: "Noi suntem poporul!" ("We are the people!"), "Armata e cu noi!" ("The army is on our side!"), "Nu vă fie frică, Ceauşescu pică!" ("Have no fear, Ceauşescu will fall"). Meanwhile, Emil Bobu and Constantin Dăscălescu were sent by Elena Ceauşescu (Nicolae Ceauşescu being at that time in Iran), to solve the situation. They met with a delegation of the protesters and accepted freeing the majority of the arrested protesters. However, they refused to comply with the protesters’ main demand (resignation of Ceauşescu), and the situation remained essentially unchanged. The next day, trains loaded with workers originating from factories in Oltenia arrived in Timişoara. The regime was attempting to use them to repress the mass protests, but they finally ended up joining the protests. One worker explained: "Yesterday, our factory boss and a Party official rounded us up in the yard, handed us wooden clubs and told us that Hungarians and ‘hooligans’ were devastating Timişoara and that it is our duty to go there and help crush the riots. But I realized that wasn't the truth."

On 18 December 1989 Ceauşescu had departed for a visit to Iran, leaving the duty of crushing the Timişoara revolt to his subordinates and his wife. Upon his return on the evening of December 20, the situation became even more tense, and he gave a televised speech from the TV studio inside the Central Committee Building (CC Building), in which he spoke about the events at Timişoara in terms of an "interference of foreign forces in Romania's internal affairs" and an "external aggression on Romania's sovereignty." The country, which had no information of the Timişoara events from the national media, heard about the Timişoara revolt from Western radio stations like Voice of America and Radio Free Europe, and by word of mouth. A mass meeting was staged for the next day, December 21, which, according to the official media, was presented as a "spontaneous movement of support for Ceauşescu," emulating the 1968 meeting in which Ceauşescu had spoken against the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact forces.

The revolt spreads to Bucharest

On the morning of 21 December Ceauşescu addressed an assembly of approximately 100,000 people, to condemn the uprising in Timişoara. However, Ceauşescu was out of touch with his people and completely misread the crowd's mood. Starting his speech in the usual "wooden language", spurting out pro-socialist and Communist Party rhetoric, Ceauşescu delivered a litany of the achievements of the "socialist revolution" and Romanian "multi-laterally developed socialist society". The people, however, remained apathetic, and only the front rows supported Ceauşescu with cheers and applause. As the speech went on, some in the crowd actually began to jeer and boo and utter insults at him. Ceauşescu's lack of understanding of the recent events and his incapacity to handle the situation were further demonstrated when he offered, as an act of desperation, to raise workers' salaries by 100 lei per month (about 9 US dollars at the time, yet a 5-10% raise for a modest salary) and student scholarship from 100 to 110 lei while continuing to praise the achievements of the Socialist Revolution, unable to realize that a revolution was brewing right in front of his eyes.

As he was addressing the crowd from the balcony of the Central Committee building, sudden movement came from the outskirts of the massed assembly, as did the sound of (what various sources have reported as) fireworks, bombs, or guns, which together caused the assembly to break into chaos. Initially frightened, the crowds tried to disperse. Bullhorns then began to spread the news that the Securitate was firing on the crowd and that a "revolution" was unfolding. This persuaded people in the assembly to join in. The rally turned into a protest demonstration.

The entire speech was being broadcast live around Romania, and it is estimated that perhaps 76% of the nation was watching. Censors attempted to cut the live video feed, and replace it with communist propaganda songs and video praising the Ceauşescu regime, but parts of the riots had already been broadcast and most of the Romanian people realized that something unusual was in progress.

Ceauşescu and his wife, as well as other officials and CPEx members, panicked, and Ceauşescu went into hiding inside the building.

The reaction of the Ceauşescu couple on the balcony is memorable: They staged futile attempts to regain control over the uprising crowd using phone conversation formulas such as "Alo, Alo" ("Hello, Hello"), Ceauşescu's wife "advised" him how to contain the situation "Vorbeşte-le, vorbeşte-le" ("Talk to them, talk to them"), and they urged the crowd "Staţi liniştiţi la locurile voastre" ("Stay quiet in your places"). In the end Ceauşescu allowed himself to be directed into the Central Committee building by his underlings.

The jeers and whistles soon erupted into riot; the crowd took to the streets, placing the capital, like Timişoara, in turmoil. Members of the crowd spontaneously began shouting anti-communist and anti-Ceauşescu slogans, which spread and became chants: "Jos dictatorul!" ("Down with the dictator"), "Moarte criminalului!" ("Death to the murderer"), "Noi suntem poporul, jos cu dictatorul!" ("We are the People, down with the dictator"), "Ceauşescu cine eşti?/Criminal din Scorniceşti" ("Ceauşescu, who are you? A murderer from Scorniceşti"). Protesters eventually flooded the downtown area, from Piaţa Kogălniceanu to Piaţa Unirii, Piaţa Rosetti, and Piaţa Romană. In one notable scene from the event, a young man waved a tricolour with the Communist coat of arms torn out of its center, while perched on the statue of Mihai Viteazul on Boulevard Mihail Kogălniceanu in the University Square.

As the hours passed, many more people took to the streets. Soon the protesters — unarmed and unorganized — were confronted by soldiers, tanks, TABs, USLA troops (Unitatea Specială pentru Lupta Antiteroristă, anti-terrorist special squads), and armed plain-clothes Securitate officers. The crowd was soon being shot at from various buildings, side streets, and tanks. There were many casualties, including deaths, as victims were shot, clubbed to death, stabbed, and crushed by armored vehicles (one TAB drove into the crowd around the InterContinental Hotel, crushing people — a French journalist, Jean Louis Calderon, was killed; a street near University Square was later named after him, as well as a high school in Timişoara). Firefighters hit the demonstrators with powerful water jets and the police continued to beat and arrest people. Protesters managed to build a defensible barricade in front of Dunărea ("Danube") restaurant, which stood until after midnight, but was finally torn apart by government forces. Intense continuous shooting continued until after 3:00 a.m., by which time the survivors had fled the streets.

Records of the fighting that day include footage shot from helicopters — sent to raid the area and to record evidence for eventual reprisals — as well as by tourists in the high tower of the centrally located InterContinental Hotel, next to the National Theater and across the street from the University.

It is likely that in the small hours of 22 December the Ceauşescus made their second mistake of the day: Instead of fleeing the city under cover of night, they decided to wait until morning to leave. Ceauşescu must have thought that his desperate attempts to crush the protests had succeeded, because he apparently called another meeting for the next morning. However, before 7:00 a.m., his wife Elena received the news that large columns of workers from many industrial platforms (large communist-era factories or groups of factories concentrated into industrial zones) were heading towards downtown Bucharest to join the protests. The police barricades that were meant to block access to Piaţa Universităţii (University Square) and Piaţa Palatului (Palace Square, now Piaţa Revoluţiei — Revolution Square) proved useless. By 9:30 a.m., University Square was jammed with protesters. Security forces (army, police and others) re-entered the area, only to join with the protesters.

By 10 A.M., as the radio broadcast was announcing the introduction of martial law and of a ban on groups larger than five persons, yet hundreds of thousands of people were gathering for the first time, spontaneously, in central Bucharest (the previous day's crowd had come together at Ceauşescu's orders). Ceauşescu attempted to address the crowd from the balcony of the Central Committee of the Communist Party building, but his attempt was met with a wave of disapproval and anger. Helicopters spread manifestos (which did not reach the crowd, due to unfavourable winds) instructing people not to fall victim to the latest "diversion attempts," but to go home instead and enjoy the Christmas feast. This order, which drew unfavorable comparisons to Marie Antoinette's haughty (but apocryphal) "Let them eat cake", further infuriated the people who did read the manifestos; many people at that time had trouble procuring such basic foodstuffs as cooking oil.

Ceauşescu falls

On the morning of 22 December sometime around 9:30 a.m., Vasile Milea, Ceauşescu's minister of defense, died under suspicious circumstances. A communiqué by Ceauşescu stated that Milea had been found to be a traitor and that he had committed suicide after his treason was revealed. The most widespread opinion at the time was that Milea had been assassinated because of his refusal to follow Ceauşescu's orders. In 2005 an investigation concluded that the minister killed himself by shooting at his heart, but the bullet missed the heart, hit an artery nearby, and he died soon afterward.

Upon learning of Milea's apparent suicide, Ceauşescu appointed Victor Stănculescu as minister of defense. He accepted after a brief hesitation. Stănculescu, however, ordered the troops back to their quarters without Ceauşescu's knowledge, and moreover persuaded Ceauşescu to leave by helicopter, thus making the dictator a fugitive. At that same moment, angry protesters began storming the Communist Party headquarters; Stanculescu and the soldiers under his command did not oppose them.

By refusing to carry out Ceauşescu's orders (he was still technically commander-in-chief of the army), Stănculescu played a central role in the overthrow of the dictatorship. "I had the prospect of two execution squads: Ceauşescu's and the revolutionary one!" confessed Stănculescu later. In the afternoon, Stănculescu "chose" Iliescu's political group from among others that were striving for power in the aftermath of the recent events.

At 11:20 on 22 December 1989, the commander of Ceauşescu's flight, Lieutenant-Colonel Vasile Malutan, received instructions from Lieutenant-General Opruta to proceed to Palace Square to pick up the president. As he flew over Palace Square, he saw it was impossible to land there. Malutan landed his white Dauphin, no. 203, on the terrace at 11:44. A man brandishing a white net curtain from one of the windows waved him down. Malutan said, "Then Stelica, the co-pilot, came to me and said that there were demonstrators coming to the terrace. Then the Ceauşescus came out, both practically carried by their bodyguards ... They look as if they were fainting. They were white with terror. Manea Mănescu (one of the vice-presidents) and Emil Bobu (Secretary to the Central Committee) were running behind them. Mănescu, Bobu, Neagoe and another Securitate officer scrambled to the four seats in the back ... As I pulled Ceauşescu in, I saw the demonstrators running across the terrace ... There wasn't enough space, Elena Ceauşescu and I were squeezed in between the chairs and the door .. We were only supposed to carry four passengers .. We had six." [2] According to Malutan, it was 12:08 when they left for Snagov. After they arrived there, Ceauşescu took Malutan into the presidential suite and ordered him to get two helicopters filled with soldiers for an armed guard, and a further Dauphin to come to Snagov. Malutan's unit commander replied on the phone, "There has been a revolution .. You are on your own ... Good luck!". Malutan then said to Ceauşescu that the second motor was now warmed up and they need to leave soon, but he could only take four people not six. Manescu and Bobu stayed behind. Ceauşescu ordered Malutan to head for Titu. Near Titu, Malutan says that he made the helicopter dip up and down. He lied to Ceauşescu, saying that this was to avoid anti-aircraft fire, since they would now be in range. The dictator panicked and told him to land.[3]

He did so in a field next to the old road that led to Piteşti. Malutan then told his four passengers that he could do nothing more. The Securitate men ran to the roadside and began to flag down passing cars. Two cars were flagged down, one of a forestry official and one a red Dacia of a local doctor. However, the local doctor was keen not to get involved and after a short time driving the Ceauşescus faked engine trouble. A car of a bicycle repair man was then flagged down and he took them to Târgovişte. The driver of the car, Nicolae Petrişor, convinced them that they could hide successfully in an agricultural technical institute on the edge of town. When they arrived, the director guided the Ceauşescus into a room and then locked them in. They were arrested by the local police at about 3:30 p.m., then after some wandering around transported to the Târgovişte garrison's military compound, and held captive for several days, until their trial.[4] On 24 December, Ion Iliescu, head of the newly formed Council of the Front of National Salvation signed a Decree on the establishment of the Extraordinary Military Tribunal. The trial was held on December 25, lasted for about 2 hours, and delivered death sentences to the couple. The execution followed immediately, on the spot, being carried out by three paratroopers with their service guns.

Footage of the trial and of the executed Ceauşescus was promptly released in Romania and to the rest of the world. The actual moment of execution was not filmed since the cameraman was too slow, and he managed to get into the courtyard just as the shooting ended.[5]

Huge controversy surrounds the abnormally brief trial put together in very inappropriate circumstances for the Ceausescu couple. Many Romanians thought the former dictator and his spouse were unjustly prosecuted and in fact murdered—and not executed as it was claimed by Iliescu's National Salvation Front—in a rush to cover beforehand potential trouble stemming from a Ceausescu previously aware of a coup d'état attempt against himself and his regime. In footage of the trial[6], Ceausescu is seen answering the "tribunal" judging him and referring to some of its members—among them Army General Victor Atanasie Stanculescu and future Romanian Secret Service head Virgil Magureanu—as "traitors". In this same video Ceausescu dismisses the "tribunal" as illegitimate and demands his Constitutional rights to answer to charges in front of a legitimate tribunal. While most Romanians shared a lot of anger against Ceausescu's regime, they recognize their former Dictator's trial as a brief, totally inappropriate one that can only be linked to an urgent desire of the alleged coup d'état perpetrators to get rid of Ceausescu.

The new regime

After Ceauşescu left, the crowds in Palace Square entered a celebratory mood, perhaps even more intense than in the other former Eastern Bloc countries because of the recent violence. People cried, shouted, and gave each other gifts. The occupation of the Central Committee building continued. People threw Ceauşescu's writings, official portraits, and propaganda books out the windows, intending to burn them. They also promptly ripped off the giant letters from the roof making up the word "comunist" ("communist") in the slogan: "Trăiască Partidul Comunist Român!" ("Long live the Communist Party of Romania!"). A young woman appeared on the rooftop and waved a flag with the coat of arms torn or cut out.

At that time, fierce fights were underway at Bucharest Otopeni International Airport between troops sent against each other under claims that they were going to confront terrorists. According to a book by Ceauşescu's bodyguard, Securitate Lieutenant Colonel Dumitru Burlan, the generals who were part of the conspiracy led by General Stănculescu were trying to create fictional terrorism scenarios in order to induce fear and to push the army onto the side of the plotters.

However, the seizure of power by the new political structure National Salvation Front (FSN), which "emanated" from the second tier of the Communist Party leadership with help of the plotting generals, was not yet complete. Forces considered to be loyal to the old regime (spontaneously nicknamed "terrorists") opened fire on the crowd and attacked vital points of socio-political life: the television, radio, and telephone buildings, as well as Casa Scânteii (the center of the nation's print media, which serves a similar role today under the name Casa Presei Libere, "House of the Free Press") and the post office in the district of Drumul Taberei; Piaţa Palatului (site of the Central Committee building, but also of the central university library, the national art museum, and the Ateneul Român, Bucharest's leading concert hall); the university and the adjoining Piaţa Universităţii (one of the city's main intersections); Otopeni and Băneasa airports; hospitals, and the Ministry of Defence.

During the night of December 22–December 23, Bucharest residents remained on the streets, especially in the attacked zones, fighting (and ultimately winning, even at the cost of many lives) a battle with an elusive and dangerous enemy. With the military confused by contradictory orders, true battles ensued, with many real casualties. At 9:00 p.m. on December 23, tanks and a few paramilitary units arrived to protect the Palace of the Republic.

Meanwhile, messages of support were flooding in from all over the world: France (President François Mitterrand) ; the Soviet (President Mikhail Gorbachev); Hungary (the Hungarian Socialist Party); the new East German government (at that time the two German states were not yet formally reunited); Bulgaria (Petar Mladenov, General Secretary of the Communist Party of Bulgaria); Czechoslovakia (Ladislav Adamec, leader of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, and Václav Havel, the dissident writer, revolution leader and future president of the Republic); China (the Minister of Foreign Affairs); the United States (President George H. W. Bush) ; West Germany (Foreign Minister Hans Dietrich Genscher); NATO (Secretary General Manfred Wörner); the United Kingdom (Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher); Spain; Austria; the Netherlands; Italy; Portugal; Japan (the Japanese Communist Party); and the Moldavian SSR.

In the following days, moral support was followed by material support. Large quantities of food, medicine, clothing, medical equipment, etc., were sent to Romania. Around the world, the press dedicated entire pages and sometimes even complete issues to the Romanian revolution and its leaders.

On December 24, Bucharest was a city at war. Tanks, APCs, and trucks continued to go on patrol around the city and to surround trouble spots in order to protect them. At intersections near strategic objectives, roadblocks were built; automatic gunfire continued in and around Piaţa Universităţii, the Gara de Nord (the city's main railroad station), and Piaţa Palatului. Yet amid the chaos, some people were seen to be clutching makeshift Christmas trees. "Terrorist activities" continued until December 27, when they abruptly stopped. Nobody ever found who conducted them, or who ordered their termination.

Casualties

The total number of deaths in the Romanian Revolution was 1,104, of which 162 were in the protests that led to the overthrow of Nicolae Ceauşescu (December 16–22, 1989) and 942 in the fighting that occurred after the seizure of power by the new political structure National Salvation Front (FSN). The number of wounded was 3,352, of which 1,107 occurred while Ceauşescu was still in power and 2,245 after the FSN took power[7][8].

Aftermath

The Revolution brought Romania vast attention from the outside world. Initially, much of the world's sympathy inevitably went to the National Salvation Front government under Ion Iliescu, a former member of the Communist Party leadership and a Ceauşescu ally prior to falling into the dictator's disgrace in the early 1980s. The National Salvation Front, composed mainly of former members of the second echelon of the Communist Party, immediately assumed control over the state institutions, including the main media outlets, such as the national radio and television networks. They used their control of the media in order to launch virulent propaganda-style attacks against their new political opponents, the traditional democratic parties, which re-emerged after more than 50 years of underground activity.

Much of that sympathy was squandered during the Mineriad of January 1990 when miners and police, responding to Iliescu's appeals, invaded Bucharest and brutalized students and intellectuals who protested what they described as the hijacking of the Romanian Revolution by former members of the communist leadership under the auspices of the National Salvation Front, in an attempt to suppress any genuine political opposition.

In May 1990, partly due to the National Salvation Front's use of the media and of the partly preserved Communist Party infrastructure to silence the democratic opposition, Iliescu became Romania's first elected president after the revolution, with a majority of 85%. These elections have been condemned as undemocratic by both Romanian traditional parties and by the Western media.

Iliescu remained the central figure in Romanian politics for more than a decade, being re-elected for the third time in 2000, after a term out of power between 1996–2000. The survival of Ceauşescu’s former ally demonstrated the ambiguity of the Romanian revolution, at once the most violent in 1989 and yet one that, according to some did not entirely replace the former regime.

See also

- Revolutions of 1989

- Braşov Rebellion

- List of books about the Romanian Revolution of 1989

- List of films about the Romanian Revolution of 1989

Bibliography

- (Romanian) —, "Sinucidere - un termen acoperitor pentru crimă" ("Suicide - a term to cover up a crime") in Jurnalul Naţional (retrieved from web site December 30, 2004; no date indicated for original publication); on the death of Vasile Milea. (in Romanian)

- (Romanian) The series of 3 articles in the Romanian newspaper Adevărul, 2003 (see archives) entitled "Eu am fost sosia lui Nicolae Ceauşescu" ("I was Ceauşescu’s double"). These are about Col. Dumitru Burlan, who also wrote a book Dupa 14 ani — Sosia lui Ceauşescu se destăinuie ("After 14 Years — The Double of Ceauşescu confesses"). Editura Ergorom, July 31, 2003.

- Mark Almond, Uprising: Political Upheavals that have Shaped the World, 2002. Mitchell Beazley, London.

- Nicolae Ceauşescu, Nicolae Ceauşescu’s speech, condemning the protests of Timişoara, broadcast on December 20, 1989 (in Romanian)

- Dennis Deletant, Romania under communist rule (1999). Center for Romanian Studies in cooperation with the Civic Academy Foundation, (Iaşi, Romania; Portland, Oregon), ISBN 9739839282. Gives a detailed account of the events in December 1989 in Timişoara.

- George Galloway and Bob Wylie, Downfall: The Ceauşescus and the Romanian Revolution, 1991, Futura Publications, London. ISBN 0 7088 5003 0

- (Romanian) Marius Mioc, Revoluţia din Timişoara, aşa cum a fost, 1997, Brumar Publishing House, Timişoara (in Romanian)

- (Romanian) Marius Mioc, The anticommunist Romanian Revolution of 1989, Marineasa Publishing House, Timişoara 2002

- (Romanian) Marian Oprea, "Au trecut 15 ani — Conspiraţia Securităţii" ("After 15 years — the conspiracy of Securitate"), Lumea Magazin Nr 10, 2004: (in Romanian; link leads to table of contents, verifying that the article exists, but the article itself is not online).

- (Romanian) Viorel Patrichi, "Eu am fost sosia lui Nicolae Ceauşescu" ("I was Ceauşescu's double"), Lumea Magazin Nr 12, 2001

- Siani-Davies, Peter (2005 (2007)). The Romanian Revolution of December 1989. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-4245-1, hardcover (ISBN 978-0-8014-7389-0, paperback).

- (Romanian) Victor Stanculescu, "Nu vă fie milă, au 2 miliarde de lei în cont" "Show no mercy, they have two billion lei [33 million U.S. dollars] in their bank account") in Jurnalul Naţional) Nov 22, 2004

- (Romanian) Domniţa Ştefănescu, Cinci ani din Istoria României ("Five years in the history of Romania"), 1995. Maşina de Scris, Bucharest.

References

- ↑ Brubaker, Rogers: Nationalist politics and everyday ethnicity in a Transylvanian town. Princeton University Press, 2006, page 119. ISBN 0691128340

- ↑ George Galloway and Bob Wylie, Downfall: The Ceauşescus and the Romanian Revolution, p. 168-169. Futura Publications, 1991

- ↑ George Galloway and Bob Wylie, Downfall: The Ceauşescus and the Romanian Revolution, p. 170

- ↑ George Galloway and Bob Wylie, Downfall: The Ceauşescus and the Romanian Revolution, p. 171

- ↑ George Galloway and Bob Wylie, Downfall: The Ceauşescus and the Romanian Revolution, p. 199

- ↑ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XKyO2G8kGM0

- ↑ Revolution, Timişoara.

- ↑ Marius Mioc, Revoluţia din Timişoara aşa cum fost, 1997.

External links

- Article on justice failing for 942 killed in Revolution on eve of 20th anniversary

- Video of Nicolae Ceauşescu's final speech in Republican Square

- Anonymous Photo Essay about the Romanian Revolution of 1989

- TV broadcasts from 22 and 23 of December 1989

- Video of Romanian Revolution of 1989

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||